Smoke without a fire – when apparent cartel activity is due to systemic issues

In March 2024 the Swedish Competition Authority (the “SCA”) received a tip from the Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (“TLV”), the central government agency whose remit is to determine whether a pharmaceutical product, medical device or dental care procedure shall be subsidized by the state. In June 2024, the SCA carried out coordinated dawn raids in Sweden (3) and, with the assistance of the Danish Competition Authority, in Denmark (2).

The SCA suspected that suppliers of certain pharmaceuticals had coordinated their pricing to regularly alternate between themselves which product the TLV would select as “Product of the Period” (the “PoP”). Interchangeable prescription drugs are grouped together by the TLV. Every month a bidding procedure takes place to select the PoP, which is the product in the group with the lowest price and availability to supply the full monthly expected requested volume. The PoP then becomes the default product that should be dispensed when a doctor has prescribed a pharmaceutical that is interchangeable with the prescribed product.

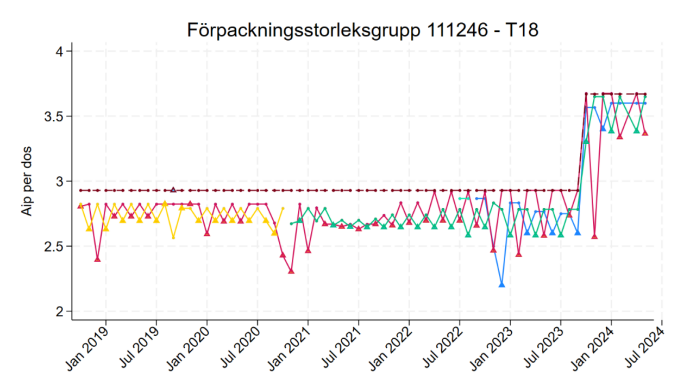

In one of the product groups identified by the tip to the SCA there were, first, two suppliers, alternating every other month to be the PoP. From the end of 2022 there were three suppliers in the product group that alternated every three months to be the PoP. The pricing development was illustrated as follows in the SCA’s decision.

In addition, documentation was received by the SCA in which references were made to when it was one company’s turn to be the PoP and that there was a specific period in time until the next time they would have the PoP. The documentation and the pricing structure allowed the SCA to carry out unannounced inspections at the companies in question.

However, after a relatively short investigation the SCA, in February 2025, concluded that it had found no evidence of any direct or indirect contacts between the competitors to coordinate price levels or rotation orders in the PoP system. The conditions for the PoP system were found to allow for what was referred to as “silent coordination” or “parallel action”. No coordination was found and the SCA concluded that a permitted silent coordination can be difficult to distinguish from a prohibited coordination. Further, it noted that the conditions for the PoP system facilitated the maintenance of higher prices than in a perfectly competitive environment. Through the PoP system, the competitors place bids each month and receive a full data set of the outcome of the placed bids for all competitors each month. This allows for market players to observe each other’s actions and can thereby adapt accordingly.

In the SCA’s press release it is stated that the SCA will continue to have a dialogue with the TLV regarding a suitable design of the PoP system from a competition law perspective. The takeaways from this case are several: (i) the SCA will not shy away from conducting dawn raids in other countries with the assistance of other competition authorities; (ii) competition can be restricted with the knowledge of the market operators but without any wrongdoing on their behalf; (iii) market operators running a fair and compliant business can still be subjected to time-consuming and costly investigations due to inherent systematic aspects that the SCA fails to identify when initiating matters in heavily regulated sectors.

Contact

Can't find what you're looking for?